The Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) is the standard that you use hundreds of times a day. it’s likely that if you’ve stumbled across this blog you must have some idea what AES is and maybe some knowledge about the characteristics of AES (It’s a block cipher that can encrypt 128, 192, 256 bits of data in different modes like ECB, CBC…) but do you know how AES actually works? I didn’t, for the longest time I’ve had the knowledge of AES but never the understanding. I also haven’t done any programming in the Rust programming language, so let’s get two birds stoned at once. Some things might seem strange, like the reliance on static arrays instead of rust vectors, but I’m here to learn, not produce a viable AES encryption implementation. You can follow along with this blog by following the code available on my github.

Some preliminaries

There are a lot of cheats to quickly compute elements of AES, but I want to learn about the mathematics on a lower level. I’ve gone ahead and oversimplified everything. I still assume some basic knowledge of things like the binary counting system, Set theory or linear algebra/matrices.

The Galois Field GF(28)

The first thing to discuss is Rjindael’s finite field, also known as the Galois Field GF(28). You might be about to click off this post after reading the name, but don’t worry. This isn’t full blown Galois theory. This is a finite field represented by 256 elements in polynomial form. For example: x7 + x6 + x5 + x4 + x3 + x2 + 1 is the last/256th element in this field. The second element is 1. If you’re perceptive you’ll have already realized it, but if not, let me re-write this: 11111111 is the last/256th element in this field. The second element is 00000001.

Addition

In cases where GF(p) and p is a prime number, we can simply treat things like addition as the same operation we would perform for the set of integers, modulo p. An exception is the case wherein p is 2 or can be expressed in the form 2n. We define operations like addition or subtraction as XOR. This is because addition modulo 2 or subtraction modulo 2 is identical to the XOR operation. The wikipedia article gives a good example to work through if you want to see get some of the intuition behind this.

Multiplication

Multiplication in GF(28) is a frequently used operation for AES. Wikipedia shows an example of multiplication in Rijndael’s field, but I opted to implement a variant of the Peasants algorithm (Steps defined in the most recent wikipedia link), this isn’t the most efficient but I felt like doing it this way.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

fn multiply_GF(mut a: u8, mut b: u8) -> u8 {

// Multiplication in GF is defined as a*b ^ p, but we use the peasants algorithm

let mut p = 0x00;

for i in 0..8 {

if 0x01 & b != 0 { // if the rightmost bit is set

p = p ^ a; // p + a

}

b = b >> 0x01;

let carry = 0x80 & a; // x^7

a = a << 1;

if carry != 0 {

a = a ^ 0x1b;

}

}

return p;

}

Of course, this algorithm carries a time complexity of O(n2), but we aren’t actually planning on implementing this in any real world situation (See Here be dragons), we just want to see AES in action.

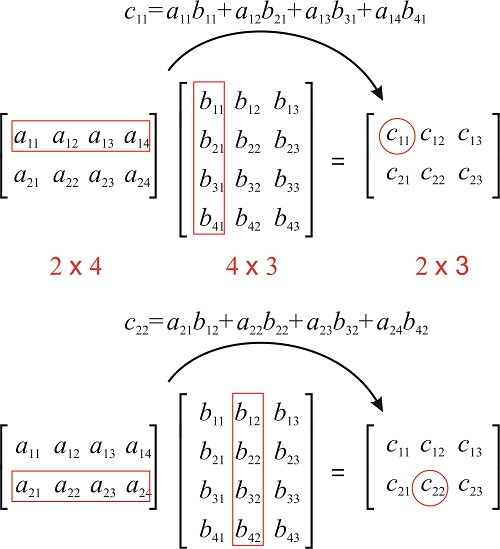

Matrix multiplication

I presume some basic knowledge of Linear algebra, and multiplying matrices is required often for AES, so if you haven’t done any Linear Algebra in awhile, I’m sure you at least remember this:

You can also read this full article. Now we can finally move onto AES.

AES overview

AES is comprised of two parts: Round key generation and the encryption itself. The encryption stage involves 10-smaller sub stages, this is to provide confusion, diffusion and dispersion (We discuss these properties and how AES provides them at the end). As a result, we need more than 1 key. Instead of sharing multiple secret keys, we share a single key and then use a key expansion algorithm to generate our set of Round Keys, K = [K0, K1, …, K10]

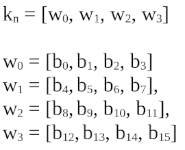

When we discuss these operations in AES, we use some specific notation. We split our 128 bit keys into a set of 32 bit “words”. Each key (Kn) can be represented as:

And all of the bytes of the plaintext are stored and represented by a matrix that we call the state array. For example, a series of bytes S = [b0, b1, …, b15] can be represented by the state:

These is what we mean when we refer to the “Current state” or “Word”.

The Key Schedule

Now we finally move onto the real fun. The Key Schedule. As stated previously, we have one pre-shared 128 bit secret, k0, that needs to be extended out into 10 more keys for a total of 11 keys. To make the next key we simply XOR the previous word, wn-1 from key kn with the equivalent word, wn, from the previous key, kn-1. The exception is the first word of a key, which is generated by XORing the last word of the previous key with the first word of the previous key. We first apply some transformations to the last word to provide a degree of obfuscation. Specifically, we apply the RotWord, SubWord and Rcon transformations:

We go more in depth and provide some examples of each of these transformations below:

RotWord

The RotWord is the simplest of the transforms. we move each character back one space, looping around on itself. i.e. [w0, w1, w2, w3] = [w1, w2, w3, w0].

My rust implementation:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

fn rot_word(word: &[u8]) -> [u8; 4] {

let mut rot_word: [u8; 4] = [0,0,0,0];

let mut i = 0;

while i != 4 {

rot_word[i] = word[(i + 1) % 4]; // a0 = a1, a1 = a2, a2 = a3, a3 = a0

i += 1;

}

return rot_word;

}

SubWord

SubWord is where things become more complicated. Here we apply the AES S-Box to each byte of the key. The S-Box is computed by first finding the multiplicative inverse of the byte in GF, then we transform the inverse using the following affine transformation:

You may want to think about this transformation as a simple mapping, mapping some 8-bit input to an arbitrary 8-bit output, with most implementations just implementing a lookup table. However, we are not most implementations. Though any real and sensible implementation would use a table, here we implement the S-Box in its full glory.

First we consider how to find the multiplicative inverse in GF(28). We note that all elements in any GF(pn) form a finite field with respect to multiplication, apn-1 = 1 when a != 0. Therefore the inverse of a must be apn-2. Don’t know advanced Mathematics, Group theory or Algebra? I recommend Chapter 6 of “A transition to advanced mathematics eight edition” by Douglas Smith & Maurice Eggen. In other (somewhat sloppy but intuitive) words:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

fn find_inverse(arr: u8) -> u8 {

// Inverse is described over GF(p^n) as a^p^n-2. i.e a's inverse is a^254

let mut result = arr;

for i in 1..254 {

result = multiply_GF(result, arr);

}

return result;

}

Now that we have the inverse formula down, we move onto the actual computing of the S-Box. We could do this using the information already given, simply multiply out the matrices, but there’s actually a more elegant definition of the S-Box. As wikipedia puts it:

This affine transformation is the sum of multiple rotations of the byte as a vector, where addition is the XOR operation

We implement this simpler form as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

fn affine_transform(c: u8) -> u8 {

let mut x = find_inverse(c);

let mut s = x;

x = x ^ left_circular_shift(s, 1);

x = x ^ left_circular_shift(s, 2);

x = x ^ left_circular_shift(s, 3);

x = x ^ left_circular_shift(s, 4);

x = x ^ 0x63;

return x;

}

Rcon

The last stage that the word must go through is the Rcon, or Round Constant. The round constant is… a constant based on the current round of key expansion you are in. A shocking revelation. Formally we describe it as:

Now, we could just once again use a lookup table to work out what the value would be at each round, as it is constant. But once again, this isn’t very fun, so instead let’s implement it as described:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

fn rc(i: u8) -> u8 { // Remember 0 counts as a number!

if i == 0x01 {

return i;

}

let rc_p = Wrapping(rc(i - 1));

if rc_p < Wrapping(0x80) {

return rc_p.0 * 2;

} else if rc_p >= Wrapping(0x80) {

let c:u16 = rc_p.0 as u16;

return (c * 2 ^ 0x11B) as u8;

}

return 0x00; // this will never be reached, but i want to make my if/else statements mirror the formula

}

Once we retrieve this value, we XOR it with the first word of our key. I also make use of Rust’s Wrapping class, which disables overflow protection on integers, as we don’t care about overflows when operating in GF(28).

We finally made it! If you’re still reading you’re nearly done with most of the hard stuff. AES’s encryption algorithm re-uses the S-box and is a little simpler (In my humble opinion) to follow than the key expansion algorithm.

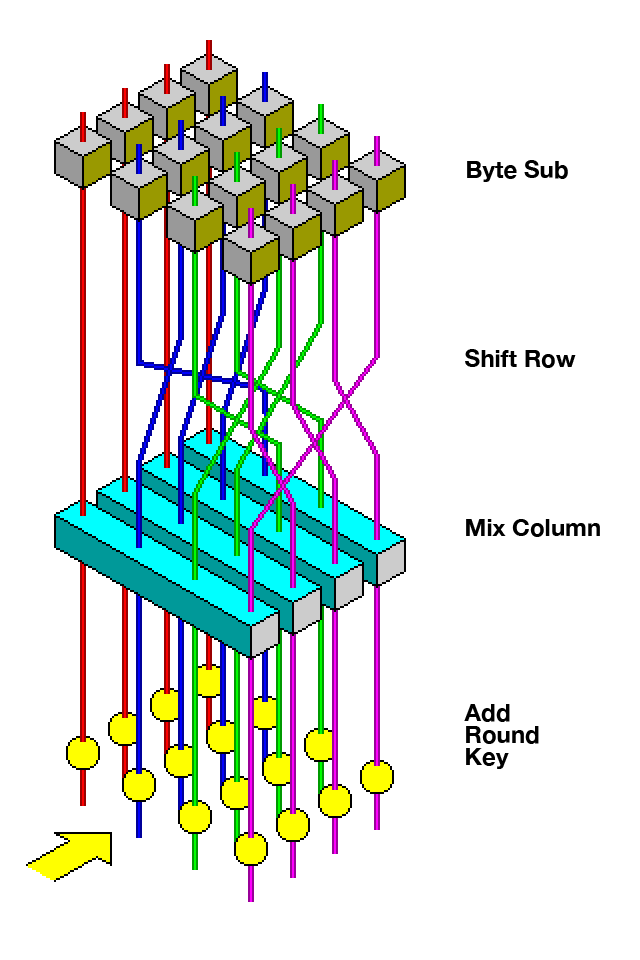

Encryption

Encryption follows a similar style to key generation. We have some input that goes through some number of rounds before producing our output:

Particularly we have four different operations: SubWord, Shift Rows, Mix Columns and adding the round key. We see the operations above. The only exception is that before the very first round we XOR the pre-shared secret, K0, with the plaintext.

SubWord

SubWord is the exact same transformation as above. We perform the S-Box on each byte in the state array:

Shift Rows

The next step mixes up the rows of the state array. This is somewhat similar to the RotWord transformation, where we simply want to shift the rows of each element in AES by 1 position. the first row is left unchanged but the second row would go from [b1,0, b1,1, b1,2, b1,3] to [b1,1, b1,2, b1,3, b1,0] and the second row would go from [b2,0, …, b2,3] to [b2,2, …, b2,1] etc.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

fn shift_rows(word: [u8; 4], shift: usize) -> [u8; 4] {

let mut word_copy = word.clone();

for i in 0..4 {

word_copy[i] = word[(i + shift) % 4]

}

return word_copy;

}

(Disregard the fact I’m calling the data “word” in this scenario, it should really be “row”)

Mix Columns

Mix Columns takes each column of the state and applies a linear transformation. This step takes in 4 input bytes and output 4 bytes in such a way that each input byte affects all 4 output bytes. Intuitively, we can see that this is possible using matrix multiplication:

By multiplying our column by this matrix, we’re ensuring that each byte effects just a single output byte. This will be important when we talk about diffusion later. We see an implementation of this transformation below (Remembering that addition and multiplication are defined differently in GF(28)):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

fn mix_columns(word: [u8; 4]) -> [u8; 4] {

let MDS: [[u8; 4]; 4] = [

[2, 3, 1, 1],

[1, 2, 3, 1],

[1, 1, 2, 3],

[3, 1, 1, 2]

];

let mut new_word: [u8; 4] = [0, 0, 0, 0];

for i in 0..4 {

let MDS_row = MDS[i];

let mut result: u8 = multiply_GF(MDS_row[0], word[0]);

for c in 1..4 {

let multiple = multiply_GF(MDS_row[c],word[c]);

result = multiple ^ result;

}

new_word[i] = result;

}

return new_word;

}

(Disregard the fact I’m calling the data “word” in this scenario, it should really be “column”)

Decryption

Now we move onto decryption. As you might expect, decryption is simply the exact same transformations but in reverse. I won’t dump all my reverse algorithms onto this page as you can easily find the code on my github. The only interesting things to note is that, in steps where matrix multiplication occurs, we must multiply by the inverse matrix to reverse the previous transformation. For example, the inverse S-Box:

Here be dragons

As an aside before my closing thoughts, I want to remind you that there is never a scenario in which manual implementation of AES will be better than simply using a trusted and open source library. This implementation was purely for educational purposes. If you want to implement AES in rust for your own project, try this package. I claim no responsibility for however bad you mess up your AES implementation and am just some dude on the internet. Always do your own research.

Closing thoughts

Now that we’ve come to the end of AES, we can appreciate some of the qualities it provides. In 1945 Claude Shannon identified that all ciphers should provide two properties: Diffusion and Confusion. Confusion means that each bit of the ciphertext should depend on each bit of the key in a way that is obscured (So that the secret key cannot be extracted from the ciphertext), while Diffusion means that if a single bit of the plaintext is changed, at least 50% of the ciphertext must also change (To protect against statistical attacks like identifying the frequency of a letter occurring).

Diffusion

Then we consider, how does AES provide Diffusion? We consider Shift Rows, which ensures that changing one bit in any column will then affect every other column and Mix Columns, which ensures that if one byte in any column is affected, it creates a knock-on effect, changing every other column, i.e. at least 50% of the data is changed.

Confusion

Adding the round key obviously adds some reliance on the key. Though simply XORing wouldn’t provide good enough protection, as if an adversary retrieves a single plaintext, they can extract the key and decrypt all subsequent ciphers. This is why we also include the S-Box which applies non-linearity and prevents retrieval of the secret key through Gaussian elimination. I won’t go into that attack just now, but I may demonstrate the necessity of the S-Box in the future by demonstrating this attack when S-Box is not present.

Dispersion

We have discussed how AES meets the Diffusion and Confusion requirements, but wait, Rjindael talks about a third property. Dispersion. This property is somewhat lesser known and simply states that nearby bytes should be moved far away from each other. This is clearly provided by ShiftRows, as each byte of each column is shuffled across the state array.

References/Further reading

Wikipedia for explaining many of the mathematical concepts and where I’ve stolen most images from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/AES_key_schedule

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Advanced_Encryption_Standard

This helpful article that simplifies some of the AES concepts:

https://braincoke.fr/blog/2020/08/the-aes-key-schedule-explained/#aes-in-summary

And of course, the most important, the original specification:

https://csrc.nist.gov/csrc/media/publications/fips/197/final/documents/fips-197.pdf