I’ve recently lost my mind. Most of you programmers know that can only mean one of two things. I’ve either been programming in JavaScript or programming in Assembly. I’ve only lost my mind and not my sense of self worth, which narrows it down to Assembly. If you’re considering working with assembly too, I just want you to know that there’s people out there who care about you and there are numerous ways to handle with these intrusive thoughts. If it’s already too late for you then continue reading to see my adventures in ASM…

Now that all the sane people have left, I’m with those who are either insane or ignorant. In case of the latter, allow me to present an introduction. In the beginning, there was nothing. Then there was the turing machine, and Alan saw that the turing machine was good. Then there was some other stuff I don’t really remember and we ended up with Assembly. An assembly language is usually identifiable by the fact that each line corresponds to one machine instruction. This means that we can’t just define a string on a single line and then use it. Instead we:

- Define the area in memory that our string is going to stay in

- Define the length of the data

- Move the message into the correct register

- Move the length of the data into the into correct register

- perform any operations required using the correct opcode, or interrupt the kernel to perform a system call

This isn’t as bad as it sounds, but is certainly a shift coming from a high level language like Python. Let’s look at an easy example.

Hello, World

asm files are composed primarily of 3 sections (though you can use more). The first section we’ll talk about is the data section. The data section is where we store our global and static variables. We signify it by placing a “section .data” line in our .asm file and then define the variables using keywords like “db”:

section .data

message: db "Hello, World", 10 ; 10 is the newline character

mes_len: equ $ - message ; "$" means current position, then we take away the address of the message to get the length of the message

“db” means that we want to reserve a single byte of data. Those of you who know the inner workings of C know that a String is simply an array of characters, each character being a single byte. This is what we’re doing in this line. Obviously “Hello, World” is more than a single byte, so instead its representation would be more like [“H”, “e”, “l”, “l”, “o”, “ “, “w”, “o”, “r”, “l”, “d”, “\n”, “\0”]. Of course, an array is a high level representation, so the variable “message” is actually a pointer to memory address which holds the binary data of each character. We also need to know how long this data actually is so that we know when to stop reading it, which is what the line starting with “equ” is for. The next section is the “section .text”, where we define our logic:

section .text

global _start

_start:

mov edx, mes_len ; Store where the bytes end for the data in the data register

mov ecx, message ; Store the reference to the message that we're going to write in the counter register

mov ebx, 1 ; Tell the base register that we want to push to the stdout

mov eax, 4 ; Move 4 into the Accumulator which is the equivalent of calling sys write on linux

int 0x80 ; int means interrupt, 0x80 means interrupt the kernel to make our system calls

mov eax, 1 ; Move 1 into accumulator, which is sys exit on linux

mov ebx, 0 ; exit code 0

int 0x80

The text section simply points to the “_start” method, so that we know the entrypoint of our program. We see in our start method that we do several operations. The first thing we do is populate our CPU registers. For the uninitiated, a CPU register is just some memory built onto the CPU, that the CPU uses to store any data it’s currently working on. There are many different types of register and I don’t have time to go into the history of all the different ones. For our use case, we first use the mov opcode to move the “mes_len” into the data register. The data register was traditionally used for things like holding the remainder when doing division operations (storing the most significant bits in the data register and least significant in the accumulator) almost simulating a 64-bit register. We can also use the data register for certain I/O operations, but here we’re using these registers with the int opcode. int means that we’re interrupting the kernel for a system call. We move 4 into the eax register (traditionally used as the accumulator) to signal the kernel that we want to perform a sys_write. We also put a 1 into the ebx to write to the stdout and put the reference to the message in the counter register, ecx. We’ve been talking about how a lot of these registers have different meanings historically vs. how we’re using them now. This is because the System calls are free to use the registers as they define them. This confusion can become a common theme when working with assembly, where there are multiple ways to perform the same function and there are changes based on architecture, OS, or the whims of God.

The last section to discuss is one we don’t use here, but will shortly. The block starting symbol section is used for variables that will be assigned and changed at runtime.

If you want to assemble and run this yourself, you can use:

1

2

nasm -f elf hello-world.asm

ld -m elf_i386 -s -o hello-world hello-world.o

nasm assembles the data into a binary file and ld links any other libraries or references, so that we only have single executable (I do not believe it is strictly necessary here, but it will be in the next section!)

FizzBuzz

Now lets move onto the FizzBuzz. If you don’t know what that is, I don’t know how you’ve made it to this point in the blog. I suppose I shouldn’t discriminate in case there are any scratch programmers reading. The FizzBuzz is a programming test with some surprising depth. A FizzBuzz program will loop from 1 to 100 and will print out each number. Except in the scenario in which the number is divisible by 3, then the word “Fizz” will be printed in its place. Another exception is if the number is divisible by 5, at which point “Buzz” should be printed. In the case that the number shares both 3 and 5 as a factor, we should print “FizzBuzz!”. You probably think you know how to do this, and you probably do, but I’d recommend watching Tom Scott’s video on the problem, which shows exactly what employers are looking for.

Now I’m not here for some fancy planning or beauty, I’m here for assembly. So let’s dive into the variables.

section .bss

fizz resb 4

buzz resb 4

iter resb 4

section .global

fizz_word db "Fizz" , 10

fizz_len: equ $ - fizz_word

buzz_word db "Buzz", 10

buzz_len: equ $ - buzz_word

fizzbuzz_word db "Fizzbuzz!", 10

fizzbuzz_len: equ $ - fizzbuzz_word

format db "%d", 10, 0 ; 10 is newline, 0 is null

The first section is the previously mentioned bss section. Here we reserve 4 bytes (or 32 bits) for the factor that “Fizz” should be printed out on, 4 bytes for the factor that “Buzz” should be printed out on and 4 bytes the the loop counter or current iteration. We then also store our strings as globals, which we did previously.

section .text

global _start

extern printf

_start:

mov dword [fizz], 3 ; set fizz to 3

mov dword [buzz], 5 ; set buzz to 5

mov dword [iter], 1 ; start on the 1st iteration

Here we see our our text section which defines the _start label and an external symbol, “printf”. This is the printf from the C standard library, but we must define that this symbol is external here and then the linker will link this symbol to the printf we all know and love. More on that later. We then perform mov operands to set our changing variables. Of note is the square brackets. These are the equivalent of de-referencing a pointer in C, without them we wouldn’t be accessing that data directly, but instead the memory location of that data. The last thing to mention is the “_start:” label. This label helps the assembler work out where things are. We can also use these to define other areas that we might want to jump to, or jump out of. This is particularly handy if we wanted to, say, run a loop:

MAIN_LOOP:

; as an aside, pushl is the same as push, we just specify that we're using a long value, which can usually be inferred

push iter ; push current iteration onto the stack (first param)

push fizz ; push fizz onto the stack (second param)

call find_remainder

cmp eax, 0 ; if we can divide by fizz

jne $ + 28 ; if it's not equal, don't bother forming the next comparisons

push iter

push buzz

call find_remainder

cmp eax, 0 ; if we can divide by buzz

je print_fizzbuzz

je $ + 48 ; jump past the next if statements

push iter

push fizz

call find_remainder

cmp eax, 0 ; if we can only divide by fizz

je print_fizz

push iter

push buzz

call find_remainder

cmp eax, 0 ; if we can only divide by buzz

je print_buzz

; Call printf.

mov eax, [iter] ; "%d" is pushed onto the stack

push eax ; The number to print is pushed onto the stack

push format

call printf

add esp, 8 ; printf doesn't clean up the stack for us, we must remove our previously pushed params

jmp increment_loop ; Not strictly necessary

increment_loop:

inc dword [iter] ; Increment iteration number

cmp dword [iter], 100

jne MAIN_LOOP

mov eax, 1 ; Move 1 into accumulator, which is sys exit on linux

mov ebx, 0 ; exit code 0

int 0x80

Now before we talk any further, we gotta discuss the stack.

The Stack

In programming terms, a stack is usually used to refer to the data structure that is a FIFO series of values that you push items into and pop items out of. You might’ve noticed the “push” operand in this section of assembly:

MAIN_LOOP:

; as an aside, pushl is the same as push, we just specify that we're using a long value, which can usually be inferred

push iter ; push current iteration onto the stack (first param)

push fizz ; push fizz onto the stack (second param)

call find_remainder

This command pushes whichever variable you give it onto the stack. This is all well and good, but what benefit does this bring us? We notice the call operand a few lines down calling something that we haven’t seen yet, referenced as “find_remainder”. This is a function that takes in two parameters and then returns the remainder after performing integer division.

We recall the previous statement:

An assembly language is usually identifiable by the fact that each line corresponds to one machine instruction.

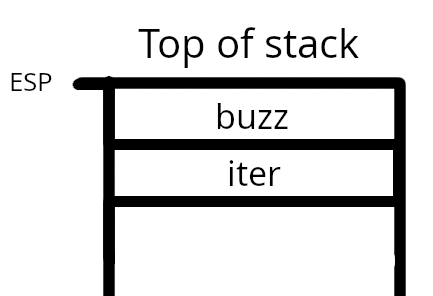

We can’t call a function AND send as many variables as we want. Instead we push our variables onto this shared area of memory. As the stack is FIFO, we can push and pop the variables without affecting variables from previous functions (As long as we don’t pop more than two variables off). After these two pushes our stack should now look like:

The stack contains the variables pushed (iter and buzz). There are also two other concepts. The stack pointer (ESP), which always points to the top of the stack and the base pointer (EBP), which points to the “base” of the current function. using these two variables we can work out where our local variables are and where our passed in variables are/return address is. Let us see what the function “find_remainder” looks like:

find_remainder:

; can either do mov eax [esp+4] to access parameter, or use base pointer, ebp, which is easier for debugging with multiple function calls.

push ebp

mov ebp, esp ; move stack pointer into base pointer

sub esp, 4 ; Align the stack to allow library calls (not needed for our use)

mov edx, 0 ; clear first 32 bits

mov ebx, [ebp+8] ; move address of the first param into ebx (iter)

mov dword ebx, [ebx]

mov eax, [ebp+12] ; move address of the second param into eax (either fizz or buzz)

mov dword eax, [eax]

div ebx ; perform eax/ebx (in our case it's eax % ebx)

mov dword eax, edx ; mov remainder into return register

; Cleanup

mov esp, ebp

pop ebp

ret

We first push the base pointer onto the stack, which isn’t totally necessary. Now our stack looks like:

We note that we now have the return address, or where the function should return to once the “ret” operand is used.

We could now push things like local variables or access our parameters, which we do by moving [ebp+8] (the return and base pointer are both 4 bytes) into the EAX register. See the code comments above. Once we have moved both our parameters into their respective registers, we perform the div operation, which divides both numbers and stores the remainder in the edx register. The eax register can be used to store a return value, so we move edx into eax and then return the top of the stack to where the base pointer is, before popping the base pointer and returning to our return address.

Conditional statements

We can now access that remainder by accessing the data register:

; as an aside, pushl is the same as push, we just specify that we're using a long value, which can usually be inferred

push iter ; push current iteration onto the stack (first param)

push fizz ; push fizz onto the stack (second param)

call find_remainder

cmp eax, 0 ; if we can divide by fizz

jne $ + 28 ; if it's not equal, don't bother forming the next comparisons

We access the eax register using the cmp compare, to compare if the eax register stores a 0. If eax does have a zero, then the remainder was zero, therefore the current iteration has the value of fizz as one of it’s factors. The CPU has a series of flags that it uses to determine the result of arithmetic operations. For example, if the two values are in fact equal, the zero flag would be set to 1. Another example would be that if the leftmost bit of the last arithmetic operation was set to 1, then the sign flag would be 1 to indicate that it’s a negative number. Using a combination of flags, we can determine the result of the last operation. We then use the various jump commands that will jump to a location based on the state of these CPU flags. In our case, we use jump if not equal. This jump if not equal jumps to $ (the current location) + 28. We choose 28 as the next compare statement takes up exactly 28 bytes of space:

cmp eax, 0 ; if we can divide by fizz

jne $ + 28 ; if it's not equal, don't bother forming the next comparisons

push iter

push buzz

call find_remainder

cmp eax, 0 ; if we can divide by buzz

je print_fizzbuzz

je $ + 48 ; jump past the next cmp statements

push iter

push fizz

call find_remainder

cmp eax, 0 ; if we can only divide by fizz

je print_fizz

We could just label the area we want to jump to, which would be better, but I wanted to do this to emphasize the point that labels are simply memory addresses and a compiler that can keep track of everything could just do this instead. With all this knowledge you should be able to interpret the entire program, but lets look at the loop and the call to printf:

; Call printf.

mov eax, [iter] ; "%d" is pushed onto the stack

push eax ; The number to print is pushed onto the stack

push format

call printf

add esp, 8 ; printf doesn't clean up the stack for us, we must remove our previously pushed params

jmp increment_loop

increment_loop:

inc dword [iter] ; Increment iteration number

cmp dword [iter], 100

jne MAIN_LOOP

mov eax, 1 ; Move 1 into accumulator, which is sys exit on linux

mov ebx, 0 ; exit code 0

int 0x80

As you may know, printf takes in as many args as you pass it. Here we simply push “%d\n” onto the stack and then the number to print. Then after the call trigger, you should see the number pop out. We then unconditionally jump to increment_loop, which isn’t actually required here as the machine would naturally tick over to that section. Regardless, it’s good practice. Let’s see if you can’t decipher what increment_loop does after reading this article, you may need to look into what the inc operand does. Full code below:

section .text

global _start

extern printf

_start:

mov dword [fizz], 3 ; set fizz to 3

mov dword [buzz], 5 ; set buzz to 5

mov dword [iter], 1 ; start on the 1st iteration

mov ecx, 100 ; run 100 times

MAIN_LOOP:

; as an aside, pushl is the same as push, we just specify that we're using a long value, which can usually be inferred

push iter ; push current iteration onto the stack (first param)

push fizz ; push fizz onto the stack (second param)

call find_remainder

cmp eax, 0 ; if we can divide by fizz

jne $ + 28 ; if it's not equal, don't bother forming the next comparisons

push iter

push buzz

call find_remainder

cmp eax, 0 ; if we can divide by buzz

je print_fizzbuzz

je $ + 48 ; jump past the next if statements

push iter

push fizz

call find_remainder

cmp eax, 0 ; if we can only divide by fizz

je print_fizz

push iter

push buzz

call find_remainder

cmp eax, 0 ; if we can only divide by buzz

je print_buzz

; Call printf.

mov eax, [iter] ; "%d" is pushed onto the stack

push eax ; The number to print is pushed onto the stack

push format

call printf

add esp, 8 ; printf doesn't clean up the stack for us, we must remove our previously pushed params

jmp increment_loop

increment_loop:

inc dword [iter] ; Increment iteration number

cmp dword [iter], 100

jne MAIN_LOOP

mov eax, 1 ; Move 1 into accumulator, which is sys exit on linux

mov ebx, 0 ; exit code 0

int 0x80

; push iter ; push current iteration onto the stack

; push buzz ; push buzz onto the stack

; cmp dword [iter], loop_end ; If iteration is equal to end, jump to end

; je end

find_remainder:

; can either do mov eax [esp+4] to access parameter, or use base pointer, ebp, which is easier for debugging with multiple function calls.

push ebp

mov ebp, esp

sub esp, 4 ; Align the stack to allow library calls

mov edx, 0 ; clear first 32 bits

mov ebx, [ebp+8] ; move address of the first param into ebx (iter)

mov dword ebx, [ebx]

mov eax, [ebp+12] ; move address of the second param into eax (Fizz or Buzz)

mov dword eax, [eax]

div ebx ; perform eax/ebx (in our case it's eax % ebx)

mov dword eax, edx ; mov remainder into return register

; Cleanup

mov esp, ebp

pop ebp

ret

print_fizz:

mov ecx, fizz_word ; Store the reference to the message that we're going to write in the counter register

mov edx, fizz_len

mov ebx, 1 ; Tell the base register that we want to push to the stdout

mov eax, 4 ; Move 4 into the Accumulator which is the equivalent of calling sys write on linux

int 0x80 ; int means interrupt, 0x80 means interrupt the kernal to make our system calls

jmp increment_loop

print_buzz:

mov ecx, buzz_word ; Store the reference to the message that we're going to write in the counter register

mov edx, buzz_len

mov ebx, 1 ; Tell the base register that we want to push to the stdout

mov eax, 4 ; Move 4 into the Accumulator which is the equivalent of calling sys write on linux

int 0x80 ; int means interrupt, 0x80 means interrupt the kernal to make our system calls

jmp increment_loop

print_fizzbuzz:

mov ecx, fizzbuzz_word ; Store the reference to the message that we're going to write in the counter register

mov edx, fizzbuzz_len

mov ebx, 1 ; Tell the base register that we want to push to the stdout

mov eax, 4 ; Move 4 into the Accumulator which is the equivalent of calling sys write on linux

int 0x80 ; int means interrupt, 0x80 means interrupt the kernal to make our system calls

jmp increment_loop

section .bss

fizz resb 4

buzz resb 4

iter resb 4

section .global

fizz_word db "Fizz" , 10

fizz_len: equ $ - fizz_word

buzz_word db "Buzz", 10

buzz_len: equ $ - buzz_word

fizzbuzz_word db "Fizzbuzz!", 10

fizzbuzz_len: equ $ - fizzbuzz_word

format db "%d", 10, 0 ; 10 is newline, 0 is null

Now you can assemble and link this with:

1

2

nasm -f elf -g fizzbuzz.asm

ld -melf_i386 -dynamic-linker /lib/ld-linux.so.2 -o fizzbuzz fizzbuzz.o -lc

Note that we dynamically link the 32 bit libraries for C “/lib/ld-linux.so.2” which points our call to printf at the right place. You may need to install the 32 bit libraries for you system if you want to run this.

Congratulations

Well you made it to the end. I don’t really know why I tried this and I don’t really know why you read this. I just have a headache. Apologies for this simultaneously over complicated and simplified explanation of assembly, but at least I won’t need to go through this again in the future.

See you next time.

:^)